Jno Didrickson is an Alaskan Native grew in Tlingit culture and lives in Turkey. He might change some of our perceptions about “Native Americans.”

Tlingit culture: How much do we know about Indians?

The word “Indian” is probably the one we stereotype the most. We often visualize that word through our experiences from western movies or Lucky Luke adventures and we enjoy dressing like indians at birthday parties or carnivals. But, have you ever met an Native American in reality? Then you may be surprised what you learn.

Interview with Jno Didrickson

Mr. Didrickson, where are you coming from? What is your origin?

J.D.: I am from Juneau, Alaska on the Pacific Northwest Coast of America called Southeast Alaska. It is located between Canada and the Pacific Ocean. Of the many tribes in America, my tribe is called Tlingit. According to our oral traditions we have been there since time immemorial, ever since before we can remember.

Your surname sounds European. Where does it come from?

J.D.: My great-great grandmother married a man from Norway named Christian Deidriksen. As Western Civilization is patrilineal our family name came from him. Although some natives were given two first names, for example John George.

So, as race you are what we call “Indian” or better to say Native American, right?

J.D.: I am a Tlingit, an Alaskan Native. As a race I am a “human being,” “Tlingit” also means “human being”. In Alaska there are many tribes, cultures and languages. For example, If you call a person from Europe “European”, they may be offended. They would prefer to be called as the country of thier origin. It is an identity, which is slowly being erased because of the stereotypes. When you group everybody in a large pool then it erases the uniqueness of each individual culture. So, as a race I am a human being; Tlingit.

We know American Natives from Western movies or from Lucky Luke adventures. And probably because of this, the indigenous people of America face many harmful misconceptions and stereotypes. I first like to make clear, what kind of people actually American Natives are.

J.D.: Sorry to say, but we are not living in nomad tents or dance around the Totem Poles as you may think. This misunderstanding is unfortunate and worldwide. We are not one big united nation. The population is now mixed with other Alaskan natives but I grew in Tlingit culture.

Can we maybe start with the clans of America?

J.D.: There are many Native American tribes and they differ from each other, not only culturally but also genetically. Before Columbus there were over 15,000 different tribes in North America. Most have their own languages. Our closest neighbor is the Haida but we cannot understand each other. These two languages are not even from the same root, unlike French, Spanish and Italian languages are all derived from Latin.

Do all those tribes built Totem Poles for example?

J.D.: There is large diversity in tribes. But we all know about the Totem Poles from movies and in those movies they do not say which tribes built those totems. The only tribes that have traditionally had totem poles were the tribes on the Pacific Northwest Coast of America, this includes my tribe, the Tlingit.

Can you tell us about Tlingit culture?

J.D.: In our tribe there are two main groups, what we call “moiety”. One is Eagle moiety, the other is Raven, which I belong to. Under those moieties are the clans named after creatures or mythical animals. Then there are big family groups under clans, called houses. My group is called Raven-Coho of the Whale House.

Ecology defines a culture. People eat different food in different regions. We have a lot of temperate rain forest and lot of wood and food. Those trees and climate decide how we live. We used to gather at dark and long winter nights and tell stories and as a reflection of those stories we depicted the animals on our belongings.

Considering the Globalization, are there enough people in the World who could carry Tlingit or other Alaskan cultures forth?

J.D.: Alaska is one of the states that has the highest Native American population. They do not live in reservations. I do not know the exact number but Tlingit culture is being carried forth. Not all but there are many who carries the traditions like me.

Are the languages being spoken?

J.D.: They are making a revitalization. Tlingit is a critically endangered language. In the World language list it is considered “rare”, because there is less then 200 people who speaks the language.

Why so?

J.D.: There was a lot of things going on; history, politics… In Juneau they speak today mainly English. The Tlingit language was earlier forbidden. My grandmother is one of those, who were taken to a missionary school and forget her language and culture. Those kids were taken from their families with an excuse to civilize them and those kids were punished when they talked their languages. They were forced to believe that being a Native was something to be ashamed.

What is the situation now?

J.D.: Even before the Civil Rights Movements of the 1960’s the Alaskan Natives started to defend their rights. Before Rosa Parks sat down in a “whites only” part of a bus, there was Aberta Schenck Adams. Alberta sat down in the Dream Theater in the city Nome in Alaska in 1944. Her protest leaded to the establishment of the first anti-discrimination law in America.

Elizabeth Peratrovich was a Tlingit, who advocated for equality for Alaskan Natives. Elizabeth’s speech in 1945 helped the passing of Alaska’s Anti-Discrimination Act of 1945, the first state or territorial anti-discrimination law enacted in the United States. Those days Alaska had not even been a State. Gradually after that the classes in native languages started. I was born in 1975 but I did not have a chance to speak my language at school.

Can you speak Tlingit now?

J.D.: I can not speak fluently. I grew up with English but took courses to learn the Tlingit tongue. The courses are quite expensive actually. If they want to save a rare language, as the politicians say, why do they charge us that much, I do not understand. Our culture was an oral culture, not written. If the language is forgotten, the culture is also gone.

What brought you to Turkey?

J.D.: I met my wife Özgür in Alaska and we moved to Turkey in 2001. Between 2010-2017 we lived in Juneau, Alaska and came back here again. Burhaniye is my wife’s hometown, where she has a close boundings. We partly live there and also in Selçuk.

And how did you occupy yourself in Turkey 20 years ago?

J.D.: Özgür is a biologist and her master thesis was about “bird migration” and together we worked for KAD (Turkish bird research society). We put rings on birds’ legs and followed their migration roads. In 2001 this was a pioneer work in Turkey but we experienced some problems and decided to leave the work and Turkey.

And what have you been doing in Turkey since 2017?

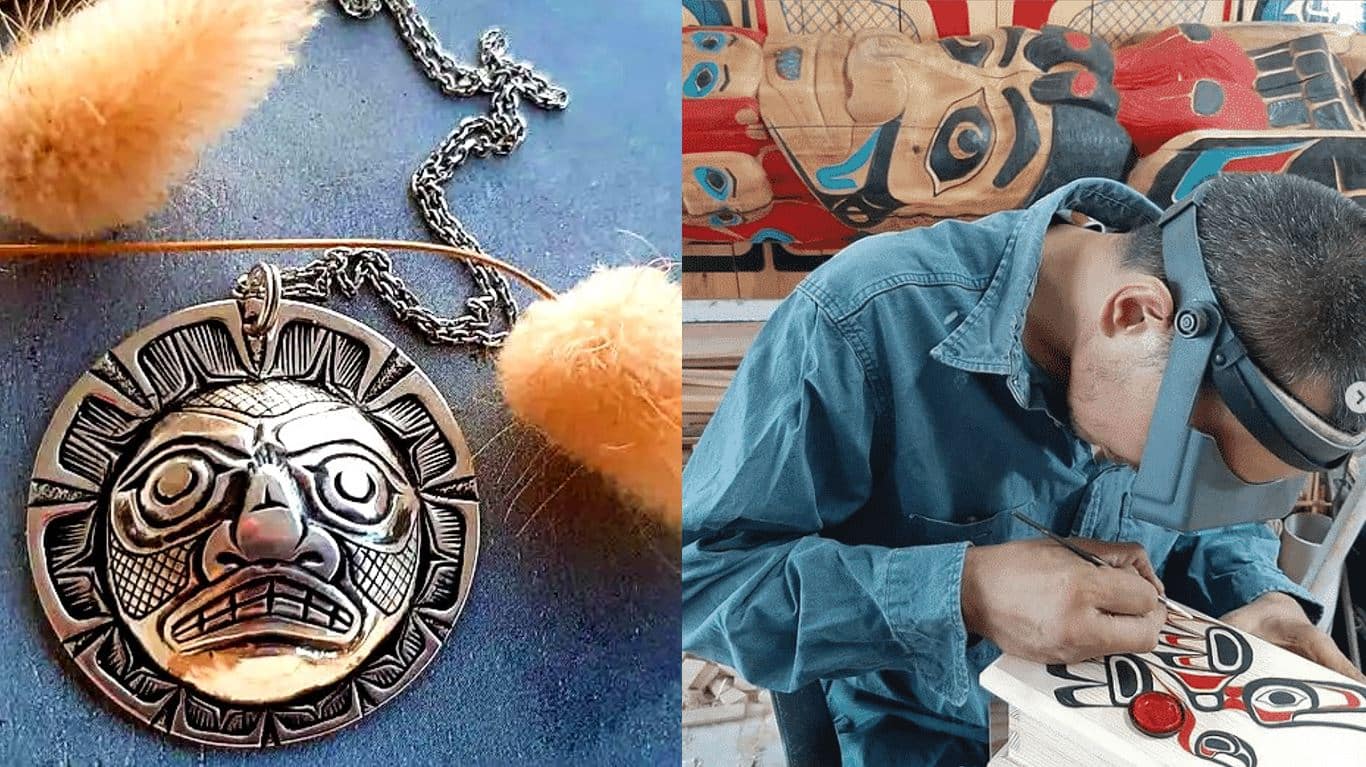

J.D.: I am occupied with my culture and cultural artwork. I had told some stories on the stage, like a story teller: the mythical and traditionally stories of my culture. Recently I am busy with handwork; carving and forming.

What kind of material?

J.D.: Here I use mainly wood and silver. In Alaska I used red or yellow cedar but here I use whatever wood is available; mainly spruce. But material is not important. The Artwork is called “form-line design”, also know as “Pacific Northwest Coast Native Art” No matter what medium you chose, the system of art is the same and has some strict rules.

What do you mean?

J.D.: First of all, there is no word in Tlingit as “art”. What you normally call art is for us the daily life. There is lots of rain there, and accordingly lots of plant and animals. As we did not have to struggle to look for food, so we had lots of time for decorating our belongings.

What do you call the work, when you carve something on a material then?

J.D.: It depends on the object. Everything we use, from spoon to canoe, we decorate to say who owns it or it reminds us of a history. Design in Tlingit usually means ownership. We do not do art in the western sense, we decorate the object we are using. It is like giving it an identity. Who owns this canoe or who is living in this house etc. Each motive has a meaning. That is also why language is important.

Your canoe peddals are quite decorative. Do you really paddle with them?

J.D.: The main vehicles for Tlingits who live the Pasific Ocean are canoes und paddels. There are two types of paddles: The functional ones, which we paddle with and the ones that are used at the rituel ceremonies. They are both decorated. At the ceremonies we dance with those paddles holding them in a particular way. You can see an an example at Youtube.

Do you also dmake Totem Poles?

J.D.: Yes, but again it is not what you think it is. When we say Totem Pole, people think of a big spiritual object. They are actually telling us a story or about a person. They have nothing to do with God or worshiping. In our language Totem is called “kuteeya” and it means “the thing done by chisel”. This is again another misinformation told about the natives.

Can you explain more about Tlingit art? What kind of patterns or tools?

J.D.: When I work on something, whatever the figure is, I usually think of a story; whether it is mythology, or it is a legend, or history. It could be even e recent history.

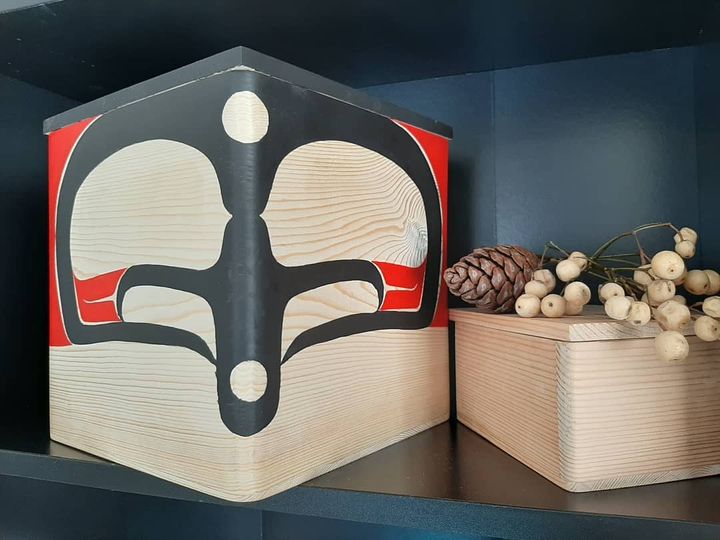

I make jewelries, boxes or such and I carve the symbols of my culture on them. I carve traditional things on non-traditional materials. As tool I only use knifes with different tops. I do not use electrical tools. With knives you would not force the wood, you can feel the tree.

As I see you make the box form without cutting the wood. Is this also a Tlingit method.

J.D: Yes, I bend the wood piece to make the corners, I do not attach the wood pieces. First I have to steam it.

Only Tlingit symbols?

J.D: Yes, being busy with those figures makes me feel like home. I am far from ocean and Alaskan forests, animals or flowers here. By carving those figures, I feel myself like in Alaska. All the artwork I do is Tlingit.

Which figure you use the most?

J.D: The symbol of my tribe, Raven, is an important figure for me. Raven lies, cheats. He is greedy and selfish. He is not devil but definetelly not good. He is kind of a reflection of the human being.

What are the meanings of those other figures you carve?

J.D: There are different ways of seeing or explaining things. It depends which clan or family you are from or which story you are telling.

The figures in our art are like pictographs. Pictograph is a picture that makes you think of something, which is a reminder of a story. The closest example I can think of is in Egyptian hieroglyphics. For example a raven on a totem pole could mean a variety of things to different people. The common thing is the raven but the way it is carved, what is next to it, what is above or below it are crucial. You have to read it in context.

Can you give an example?

J.D: My aunt has just passed away and so I carved her a box. All I was thinking of while I was carving the box was her, her family and her life. And if you do not know this information, then all you see is the animals. You would not see any trace of her daughter or brothers.

This is actually what the art originally was but today the art is mainly optic.

J.D: That is why we do not have a word for art. Art for us is not something to hang on the wall.

How did you learn this art? I mean forming material, carving and painting the figures?

J.D: I learned in the streets. When I was growing up, there were at least couple of people around me doing this. This art has never died actually. The way I learned is just watching and observing those people. I normally learn by observing, without asking question.

Since when have you been doing this art?

J.D: Since I was 9. I started to do it for commercial purpose in Alaska, namely for living. When me and my wife were living in Alaska it kept us going economically. Those years the economy collapsed in Alaska, there were no jobs. So this art saved us.

You are a unique person in Turkey. How do the Turkish people react when they meet you?

J.D: They say that we are relatives, which is not true. This maybe a trick to start a conversation but I find this weird. I would not even call myself Indian and some calls me cousin and some of them want to touch me.

Nobody asks me from which tribe I am from. Indian is Indian for them. I see that people like Indians but if so then one should learn more about what you are interested in. Then they would see that there are many different Indian tribes.

There are differences in cultures. If you only say Turkish, not mentioning for example Aegean or Black See, then you miss the beauty and differences between those regions. When you only say Turks or Indians then you ignore the richness, the culture and the diversity.

What do you think about Turkey?

J.D: Interesting place. I like Turkey a lot because of its history. Civilization was first born here. Entirely different culture, friendly and welcoming.

And how can we find outmore about your handcrafts?

J.D: At Art ve Craft onlineshop or at my social media accounts Instagram and Facebook .

About Jno Didrickson

Jno Didrickson was born in Juneau, Alaska in 1975. He is a Tlingit of his mother’s clan, the Luk’naxadi (Raven-Coho). His father is of the Deisheetan (Raven-Beaver) clan. His interest in native artwork began at a very early age. Jno is a self-taught wood carver having watched his aunt and other master carvers practicing their craft. He strives for a traditional look to his original designs by studying older designs. His exhibition titled “Alaska native art” which was sponsored by US Embassy and US Consulate İstanbul was shown in İstanbul, Ankara, İzmir and Burhaniye between 2008-2010. Jno currently resides in Turkey where his wife is from.