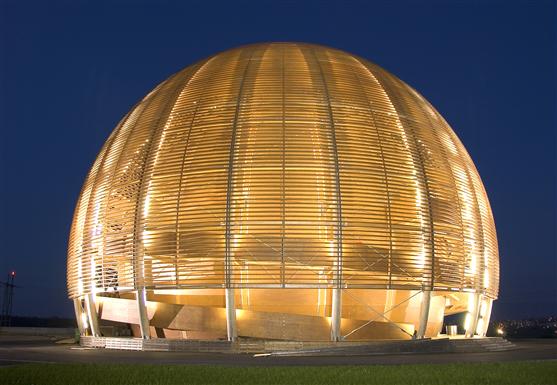

The European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) is carrying out one of the greatest experiments in the history. There are numerous unanswered questions about the research, including ‘the God particle’ discovery and anti-matter. We reached James Gillies, the Head of Communication Spokesman at CERN, and derived our questions from our readers’ curiosity to cover the overall process about this great experiment.

“Our experiments at CERN take us very close to the Big Bang, but we do not attempt to explain the creation of the Universe. Our research is about understanding the evolution of the universe, its behaviour today and its future development.” – James Gillies

Interview

Translated by Engin Doğalı Yıldırım

In fact, we know this through media, but we would like to hear the official dialects. And so we would have made an entry. How many scientists work at CERN? Could you please name member countries contribute to this project? How do you finance?

James Gillies: CERN has around 2,300 staff, and some 10,000 scientists from people around the world who come here to use our facilities. At present, our ‘member states’ are Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. Romania is a candidate for accession. Israel is an ‘associate member’ in the pre-stage to the membership. India, Japan, the Russian Federation, the United States of America, Turkey, the European Commission and UNESCO have ‘observer’ status. Our budget is provided by our member states, who each contribute according to their net national income. The percentage contributions of the member states are recalculated each year.

Although there is such possibility to the lack of definite evidence, why does Europe spend such a giant budget for this experiment/project? Why is this project so important?

James Gillies: CERN’s annual budget is actually rather modest: the equivalent of a single large research University, and it is distributed among our Member States. In exchange, our Member States get world leading research in fundamental physics, a powerful force for innovation, an important training ground for scientists and engineers, and a vehicle for peaceful collaboration among nations.

How do you upload/record the data with what kind of a technological system?

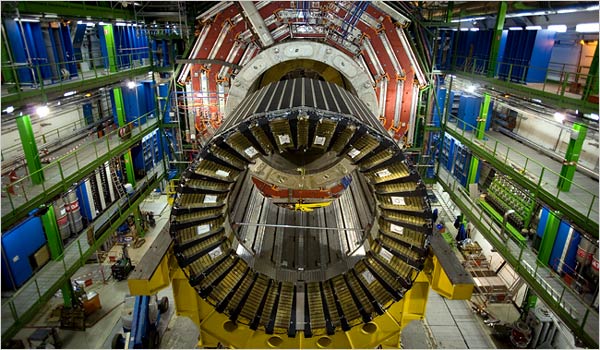

James Gillies: The Large Hadron Collider will ultimately collide bunches of particles at a rate of 40MHz. Today, we are at about half of that. Each time bunches collide, several individual proton-proton collisions happen, spraying new particles into particle detectors. These instruments contain up to 100 million readout channels, so you can imagine the amount of data that is produced. It would be impossible to store it all, so the first stage of data processing is spotting the potentially interesting collisions and flagging them to be recorded. All but 200 bunch collisions per second are rejected. Nevertheless, the LHC experiments record petabytes of data each year. All of this data is stored on tape at CERN, with subsets stored at other locations on the Worldwide LHC Computing Grid. This is the system we use to store and analyse data. There are about 10,000 processors at CERN, and about ten times as many elsewhere on the Grid. To LHC scientists, the Grid makes it look as if all the data and all the processing capacity are in their own computers.

The experiment is so called as ‘God Paricle’ in Turkish. This creates a perception that God created the universe. Do you have a link between the Big Bang theory which tries to explain the first occurrence of the “universe” and the “creator?”

James Gillies: The label God particle came from a book written by Leon Lederman, but the particle it refers to, the Higgs, has nothing to do with God. I think it’s been given that label because of the vital role it plays in particle physics. Without it, or something that does the same job as it, the Universe would have evolved in a very different way, and the kind of matter we’re made of would not exist. Our experiments at CERN take us very close to the Big Bang, but we do not attempt to explain the creation of the Universe. Our research is about understanding the evolution of the universe, its behaviour today and its future development.

What is the relationship between Big Bang theory and CERN’s experiments? Is it possible to reproduce/recreate the Bing Bang theory in an experimental environment? From this point, what does your experiments at CERN aim to know what about the universe? Could you briefly name them?

James Gillies: Our experiments reproduce the conditions that existed a millionth of a millionth of a second after the Big Bang. That may not sound like much, but to a particle physicist, most of what’s interesting in the history of the Universe happened right at the very beginning. The questions the LHC experiments are addressing include elucidating the nature of mass, looking for the dark matter that makes up about a quarter of the Universe, investigating why nature has a preference for matter over antimatter, and studying matter as it would have been just after the Big Bang.

What if the CERN experiments cannot discover the Higgs boson (also publicly known as God particle) which is necessary for the transition from non-existince to the material (substance) form, can we say that the whole theories will be a waste in phsyics? What is your take on?

James Gillies: Whether we find the Higgs boson or rule it out altogether, it will be a major discovery. The mechanism proposed by Peter Higgs and others in the 1960s is just one possible explanation for the mass of fundamental partilces, but there are others. One manifestation, for example, would not only allow us to complete the so-called standard model, which describes the behaviour of fundamental particles, but would also lead us into physics beyond the standard model, possibly accounting for dark matter.

Aside to the LHC researches, today’s technological advancements contribute a lot to Science. Regarding the cutting edge technologies, where has mankind reached so far? Do you have any projection?

James Gillies: I don’t want to make predictions, but there will certainly be applications of the discoveries made by the LHC experiments. What I can say is that there are already applications of the technologies developed for the LHC. To give two examples, the ultra high vacuum techniques developed for the LHC are now used to improve the efficiency of thermal solar energy collectors, and electronics developed for one of the LHC experiments has allowed medical scanners combining the complementary techniques of PET and MRI.

Do you receive support from any religious foundations or societies, Vatican per se? On the Internet, I came across with a point of view, which claims CERN experiments will cause a big vortex in the final date of Mayan calendar and that means the return of Jesus Christ on Earth. How do you interpret those kinds of scenarios? Do these scenarios annoy you?

James Gillies: We do not receive support from religious foundations, and we do not take the hype surrounding the end of the Mayan calendar seriously. The interface of science, philosophy and the world’s major religions, however, is a subject that interests me greatly, and CERN will be participating in an event later in the year that examines this subject.

There is a scientific research on a popular TV show, LOST, which is called Dharma İnitiative. There are underground labaratories. What do you think about those kinds of references/ascriptions purpose to link CERN with a TV show? Do you find an anology/similarity between movies, books and real scientific works?

James Gillies: I’m not familiar with LOST, but in general I welcome science in popular culture. Don’t forget that CERN worked closely with Sony Pictures on the screen adaptation of Angels & Demons. We live in an increasingly science and technology based word, so it’s important for science to engage with society. Science in popular culture is one sign that this is happening.

Not all scientists support or believe in CERN’s experiments. On the other hand, it is quite obvious that people like armageddon stories. If there will be an incalculable variation in CERN experiments, would this situation be resulted a kind of destruction on Earth? Can a blackhole be created in the space or on the earth? How can you interpret these scenarios? And can you say ‘there is nothhing to worry about, everything is under control’? Or could you say that CERN’s experiments have nothing to do with these scenarios?

James Gillies: The LHC is perfectly safe, and there is no chance at all that it will do anything dangerous to the Earth. We know this because the LHC does no more than reproduce conditions in the laboratory that we already observe occurring in nature. Bringing such conditions into the laboratory allows us to study them.

Let’s say the day has come, and you found out all the answers that you were looking for. What would be that ‘major change’ for the sake of humanity? Do you have any projection or prediction regarding technological developments and advancements?

James Gillies: CERN science has consistently delivered technological advances in all walks of life. I’m sure you are aware that the World Wide Web was invented here, but that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Particle detection techniques developed at CERN in the 1960s have revolutionised medical and security imaging, and our cutting edge requirements are always driving forward the capacity of information technologies. As for applications of our discoveries in fundamental physics, I don’t want to make any predictions. I’ll just point out that without the major advances made in physics around the turn of the 20th century, we’d have no telecommunications, no modern electronics, no GPS. Human ingenuity always finds applications of basic science eventually.

[divider]